For the Love of Limestone

Geology is hard. Really attempting to comprehend the scale of any geological process requires an intellectual breach that challenges us to reconcile our perception of the relatively static world we observe with formations that were created an incredibly long time ago over an enormous number of years that are effectively impossible to imagine. It’s like trying to picture either the number of stars in a galaxy or molecules in a glass of water – but for me, limestone is even more difficult still.

Limestone is an organic sedimentary rock; meaning that is is mostly made up of the remains of living things that lived, died, accumulated and were buried deep and long enough to become lithified (compressed by the pressure of the weight of the rock and sediments above it into solid rock, basically). Coal is one of the other more common examples of an organic sedimentary rock, which (as we remember from grade school) is composed mostly of plants that accumulated in swampy forest environments and were buried, compressed and lithified deep within the Earth. In the case of limestone it is the skeletal remains of living creatures that lived and died in a long ago oceanic environment that make up the bulk of this rock type. Further still, limestone and other carbonate rock dominant (karst) environments cover about 15 percent of the Earth’s land mass and are distributed widely, making it an absolutley worldwide phenomenon. So not only is that 500 foot tall cliff exposure you are looking at almost entirely made up of dead marine animal skeletal fragments, but similar rock types occur globally.

Fossil Brachiopod embedded in limestone in eastern Arizona

The world in which these animals lived was a very different place. All the continents were either connected together or very close to each other in this warmer, more humid and oxygen rich environment. Tropical seas flooded large swaths of the continents, creating the warm, shallow seas (picture the Bahamas or Australia’s Great Barrier Reef) in which these creatures lived – corals, crinoids, brachiopods, bivalves and tiny foraminifera were some of the most common of these animals.

Crinoid stem fragments in Grand Canyon National Park

Criniod (also called water lilies) have the general morphology of a flower – a foot attaches to the sea floor and a stem made up of small circular plates leads to what looks like a flower at the top where most of the animals vital parts reside, including arms that look like flower petals that are used to grab food. Though still living today, crinoids were much more abundant in these ancient oceans.

Fossil crinoid calyx (the bud and flower at the top) surrounded by other crinoid fragments. This individual is frozen in time with its arms folded back, exposing the mouth (in the center) and its butt (the dark circle off-center above and left of the mouth), understandably making this my proudest fossil discovery to date. Imagine if we were built this way – mouth so close to the butt…

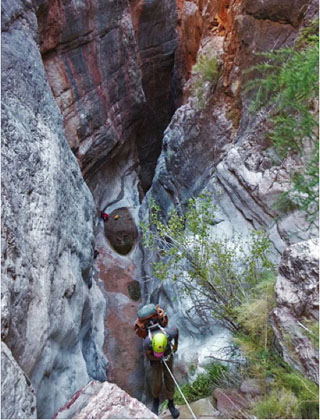

Redwall limestone narrows in Grand Canyon

The sediments of Redwall limestone were deposited around 340 million years ago in the Mississippian subperiod, in the early Caboniferous period. Monsters inhabit this world, but dinosaurs won’t evolve for roughly another 100 million years. Instead of dinosaurs, the seas are terrorized by giant sea scorpions up to 7.5 feet long and seven-foot long millipedes roam the primitive forest floor. Vertebrates are just getting a foothold on dry land and life makes a great leap forward towards terrestrial domination with the evolution of eggs with a hard, mineralized shell for protection. Most of the world’s coal deposits are created by those swampy forests during this period as well.

![]()

Daniel Elson rappelling into the Redwall narrows of Cove Canyon – GCNP

Every rock has a story to tell – rich with the marks of a previous world. Limestone is special in that it is made from the very living things of this lost world, laid bare in what they have left behind. Ponder the significance of this unassuming grey stone as you traverse a water-carved hallway of history, hike through a 500-foot deep tombstone, a monument to the power of time and to the utterly countless lives that helped make this world the marvel that it is.

Pat Winstanley

Your membership makes a difference!

We regularly deal with land managers, national park officials, and politicians. The broader our membership base the greater our impact.