American Canyoneers Toroweap Cleanup Project

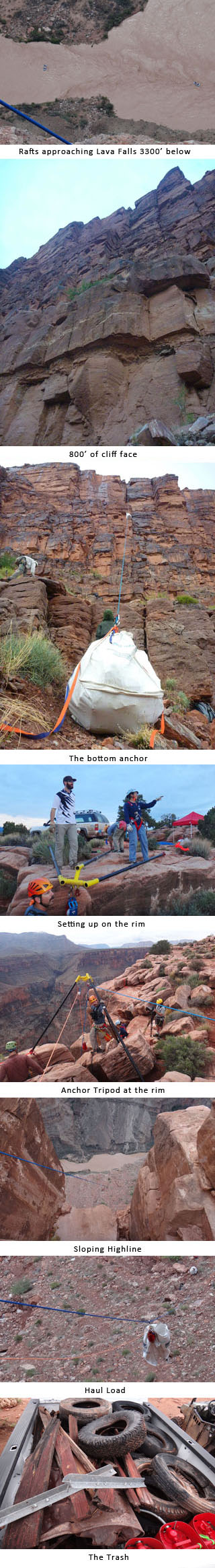

There are some silly traditions in the world. Apparently one of them is to roll tires off the rim of the Grand Canyon, hoping to make it to the Colorado River 3300′ below. Often times they were lit on fire and then tossed. Over the past 5 years, the Toroweap park ranger had noticed a dozen tires plus a variety of other debris at the base of Toroweap Overlook (www.nps.gov/grca/planyourvisit/tuweep.htm). The Toroweap Overlook sits on top of the Esplanade sandstone layer with four distinct limestone or sandstone layers above. Below are eight layers before getting to the river. Not far downstream of the overlook is Lava Falls. It is one of the largest and most difficult rapids in the Grand Canyon. It is not actually made of lava despite significant volcanic activity in the Toroweap area. It is quite difficult to get from the overlook to where the trash has come to rest. Hence it was not safe to try to carry the trash up to the Toroweap Overlook. It would be even more dangerous and difficult to attempt to take the trash to the river to be picked up by rafts. Raising the trash 800 feet up a vertical cliff seemed to be the best approach.

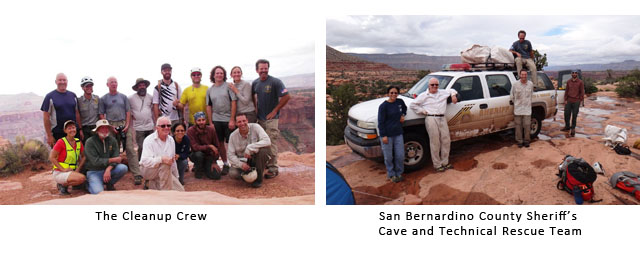

NPS ranger Todd Seliga contacted American Canyoneers (www.americancanyoneers.org), concerning a cleanup project. American Canyoneers has been active in various conservation projects around the western United States. I am a member of American Canyoneers. I volunteered the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Cave and Technical Rescue Team (www.caverescue.net). Five members from the Cave team gathered about 3/4 of a mile of rope and other technical equipment and drove 9 hours to assist American Canyoneers and Grand Canyon National Park. It should be noted, the San Gorgonio Search and Rescue Team from San Bernardino County allowed us to use two 1000-foot rolls of 12.5 mm rope.

We set up an artificial high directional tripod at the edge of the cliff. As best we could we estimated the line between the bottom anchor 800 feet away, the tripod at the edge, our top anchor (a Suburban parked sideways 30 feet from the edge) and a tree 60 feet behind the Suburban to be used as a second anchor for the haul. We were mentally prepared to move the tripod or Suburban. In fact, due to potential hot weather and logistics of setting up the system, we started at sun up in order to have the full day. We were shocked that our first attempt lined up well. We did not have to make any adjustments. The biggest challenge was just getting the rope to the bottom anchor. This is not a shear cliff. Rather, it is stair stepped with at least two ledges. We tried twice to throw a 5 mm Spectra messenger line to the bottom. The second time from a different location, resulted in the line being stuck. We could not pull it up. Hence our plan to use a giant sling shot for the third attempt was out. Instead we sent a person down on rope. That turned out to be ideal. On the way down, he dislodged a tire much higher than the rest. It rocketed down the slope toward the river. It stopped not too terribly far below the others. It alerted us that we potentially could release rock that could make it to the river, 2700 feet below the overlook. After that we stationed an observer upstream to warn of approaching rafters. We would stop the operation until they passed our location.

With three people at the bottom, one descended by rope and the other two by a treacherous route, they built a huge anchor. They used a large construction bag that holds rock or rebar. They built a dead man that could support a sloping highline with the resulting large forces. They shared this space with a rattlesnake that initially crawled over the rope. The three would scramble up and down steep, loose rock slopes to find the trash. Some of it was very heavy pieces of metal. They also found a snowboard and even located two hats and a camera bag that probably were not purposely thrown down. Whenever there was activity from above, they would have to hide under large ledges to be protected from rock fall.

Besides the five Cave team members, there was one ranger, two national park volunteers and six members from American Canyoneers. With this much people power, we were able to do a “Georgia” haul. We simply had five or six people pull up rope to raise the load. There were had seven loads and it took 11 resets per load which means we raised a total of about 5,600 feet.

Getting over the edge with a second construction bag was the most difficult part of the raise. We had to modify the attachment system after the first raise. The other six went pretty well. Depending on the weight of the load, it took between one to three edge tenders to get it over. The trash filled up the bed of a pickup truck. Park volunteers burned some of the wood that night.

There was one eventful period as a storm rolled through. It was complete with wind, rain and lightning. As it approached, we removed any metal we were wearing and took shelter in automobiles. The three people below stayed under ledges, analyzing the amount of metal in their umbrellas. Fortunately there were no lightning strikes in close proximity. After about 40 minutes, we were able to resume the raise. Unfortunately we had placed a huge gear cache in line with the flow of muddy rainwater.

The work was done by early afternoon, giving us plenty of time to enjoy the Toroweap area and a great meal provided by Rich Rudow and Moenkopi Riverworks, a river outfitter.

Thanks go to the following individuals who participated.

National Park ranger: Todd Seliga

National Park volunteer: Bob Carpenter

American Canyoneers:

Paul McDaniels, Jef Funch, Tom Jones, Angela Horvath, Rich Rudow, Marlowe Quart

Cave and Technical Rescue Team:

Robert Hill, Calius Lawrence, Sonny Lawrence, John Metzger, Trevor Walton

Report: Sonny Lawrence

Photos: Sonny Lawrence and Rich Rudow